Day Two of Prague: Rise and Shine! After seeing Alphonse Mucha's Art Nouveau stained-glass painting at St. Vitus Cathedral, we took a small detour and paid his mini museum a visit. But first, we went to see the Dancing House, a seeming Seussville house come to life for a quick photo. After gettin' jiggy with it, we hurried back to Nove Mesto or New Town Square. Unlike Stare Mesto (Old Town Square), Nove lacks charm and character though tries to make it up with its stretch of branded shops and stores. There were a few kielbasa stand's at the end, but nothing that stood out for us to linger further. That, or we were just too excited to see Mucha's work.

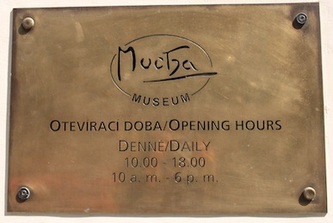

Fortunately a few blocks away from Nove Mesto, we reached the Mucha Museum early enough to spend time ooohhh-ing and aahhhh-ing at his anime-ish, pastel paintings. The museum, dissimilar from any we've seen, is relatively small. A 20-minute video of Mucha's life routinely plays at the back of the site while the rest of his work, hangs simply on ivory walls yet leaving us wanting to see more. The paintings were absolutely unique and beautiful. Wrapped in flowers, vines, flowing dresses, fading pastel colors, and evocative women, Mucha's work is easy on the eye and inspires anyone who sees it. Some of his works are posted at the Mucha Foundation website, which contains more information and details about his life and works. After Mucha, we went straight to see Prague's Jewish Quarters. Debated on whether to go inside the sights or not, we finally bought our tickets at a queue-free souvenir shop across the Old-New Synagogue. The Old-New Synagogue, the oldest in Europe, stands out from its neighboring Nouveau-painted buildings with its serrated gables and rice roofing brought together by its brick red, tawny and rusty hues. The synagogue's nave interior was simple. Backdropped with high ceilings and narrow windows, it comes with a wood wall-seating good for maybe forty people, the bimah in the middle and the elaborate Ark housing the Torah. The Klausen Synagogue and the Ceremonial Hall, situated near the Jewish Cemetery, exhibit Jewish traditions and festivals. We visited the Ceremonial Hall first where it presented burial customs. In Jewish law, the dead is never left attended until the person's buried as a sign of respect and burials preferably happen within a day or two after the time of death. It's also customary to leave stones and even pieces of paper containing prayers on top of their headstones (as we've later seen in the cemetery) as a remembrance of them. In addition, many Jews enter the field of medicine, not solely because for their love of science but a Sacred Duty to help those in need.

While the Hall focuses mostly on a person's death, the Klausen Synagogue presents the Jews' everyday life - birth, circumcision, marriage and festivals. Upon presenting our ticket, we were welcomed by a charming old man, sitting behind the ticket counter while picking his nose with his pinky, eyes closed. Ralph and I, grinning ear to ear, dared not disturb his ritual. "Halo!" he finally greeted, now wide-eyed. "Halo!" we responded, still grinning as we walked past him and inside Klausen. Obviously newer than The Old-New, the Klausen looked more like a museum than a synagogue. It exhibited some circumcision tools, kitchen wares, religious items, wedding gifts and even a chuppah! The breaking of the glass in a wedding ceremony is said to be reminder of the sadness and destruction of the Temple, and should be remembered even in the midst of jubilant festivities. Mazel Tov!

Prague, Czech Republic in Pictures For dinner, we ate at one of the most beautiful cafe's I've ever seen - Kavarna Obecni Dum at the Municipal House. It's high ceilings, light and airy colors, wooden tables and chairs - makes up its Nouveau interior. Surprisingly affordable, we ate a meal of omelette's, soups and side veggies. Food and ambience was great but the service, not so much. Our aggressive waitress was rude and totally off-putting. With two hours to kill before the light show at 8PM, we finally enjoyed the rest of Old Town Square, where the Astronomical clock, Easter shops and Trdelnik, roasted cinnamon bread, abound. We capped the night with the long-awaited Image Theater's, Afrikannia, a story of a married couple vacationing in Africa. The show had an open-seating and was immediately filled. But the elevation of its seats failed to consider people 5' and below. Sitting beside two kids, we practically had to crane our necks above the crowd for the whole time to the dismay of those behind us and the unnecessary guilt of those in front. Thanks to this one minute clip from Image Theater's Youtube Channel, I can relive a short part of it in the comforts of my own home.

Tram 22 was predictably jam-packed by tourists but we didn't mind. Public transportation has always been part of our Euro adventures, a must-do in every city. The dread of getting completely lost, the anxiety of going around in circles, the pressure of time and the satisfaction of finding our way yet again always roll up in one big ball of unforgettable memories. And by the time of our Prague visit, we were masters of navigating the thousand rails and bus routes, and the art of squirming through lines and crowds. So when Ralph and I found ourselves hanging on tram poles and handlebars sandwiched between unfamiliar, sweaty faces, we knew Prague was going to be a walk in the park.

That early April morning day started a bit fickle, the undecided sky trotted back and forth whether to concede to the threatening heavy clouds or succumb to the sun's mighty light. Though scattered light showers came over the city, it miserably failed to deter us or the throngs of aviator-wearing, camera-ready peeps from taking Prague Castle by storm. Like the Buckingham Palace, nutcracker-esque guards in carefully ironed uniforms stood outside their rectangular-shaped shed, stiff and annoyed, perhaps, by the thought of their faces plastered all over Facebook or blogs. The towering spires of St. Vitus Cathedral, one of the three chapels of the castle, commanded attention and hovered over us as we obligingly craned our necks to appreciate its beauty. Mixture of grays, creams, greens, yellows and blacks color its facade, making it look like an aging yet stylish castle of its own. Its various gargoyles adorning the walls patiently wait to spill water away from its variegated marble. We opted out of the tour and enjoyed the stained glass nouveau and the neo-gothic interior from the designated space barricaded by steel stanchions serving as the chapel's lobby. By lunch time, we had toured and taken pictures of the castle grounds, and had reached Wenceslas Square, where a four-man orchestra serenaded the crowd while we waited for the castle's so-so changing of the guards. After the castle, we crossed the buzzing Charles Bridge running across Vlatva River. Connecting Prague Castle and the Old Town Square, Charles Bridge is unsurprisingly overcrowded with tourists and locals alike. Not only do vendors, mostly painters selling their Prague portraits at a slightly higher price, populate the place but interesting statues backed by legends, myths and twisted facts spanned throughout. The most famous statue, St. John Nepomuk's, is said to bring good luck if its bronze tripartite base is rubbed. Having seen enough for our first day, we briskly visited Old Town Square in search of the Black Light Image Theater. Off of the main square, we spotted its simple, lemon sign hanging above in black poles. Ticket's reserved for tomorrow's show, we headed back to our modern and clean hostel/hotel to unwind, in anticipation for another backpacker's day - Nove Mesto, Mucha's, Jewish quarters, Dancing House, Municipal House, Stare Mesto and of course, the light show.

Auschwitz II or Auschwitz-Birkenau is ten times larger than the first, though vaguely similar yet magnified in purpose. Dusty and wide, its red buildings unsurprisingly resembled Auschwitz I. Its acres of grassy land, fenced in by lengthy barbed wires masquerade like a recently developed park waiting to be filled with graffiti. When we arrived, other tour groups were already huddled in a specific area - some caught in a trance of I could only imagine, caused by the horrific stories of camp life, while some, shaded away from the sun's prickling light, loitered under the main entrance. We walked past the fading gate popular for its appearance in Schindler's List to be welcomed by two railway tracks. We would later find out its main purpose - one for incoming prisoners, the other, for picking them up. To its right lies the washed-out carmine barns, some of it carefully preserved while others show marks of it going up in flames.

Reluctant to lose any time, our guide led us to the first shelter known as the prisoner's communal toilet. Hitler and his men with their deranged idea of racism really thought little of their prisoners. Empty and hollow, long trenches with cemented toilet openings act as the camp's urinal. It was the poorest living conditions at its finest. Lined up, thousands of prisoners were only given a few minutes to use them during specific breaks, otherwise, they do not get to use them at all. Some prisoners also worked here, scooping out the mushy feces of their relieved fellow inmates. Ironically, this is one of the "best" places to work around the camp - the Nazi's, afraid of catching diseases, left the workers to themselves and stayed away from it. The camp dorms looked exactly like the communal toilets outside, while exchanging its shoddy concrete urinals into tightly squished bunk beds. No fancy wallpaper or elegant furniture, just some thin roof, thin walls, and cheaply made bunks of three. Straws were the only bedding used and rats, a nasty companion. Eight or more prisoners slept on each bed, whom were often caught fighting to secure their place on the top bunk. Bathroom or bathroom breaks during bed time were prohibited, which means, the ones on top misses out on the flow of piss and the slow slump of excrement throughout the night.

As we moved out into the field, we walked towards the railway tracks that greeted us where a windowless railcar stood. This, our tour guide said, is one of the original cars used to transport the Jews into Auschwitz, mostly Hungarian Jews. Packed with prisoners, thousands of deaths occur here even before it reached Auschwitz - suffocation and starvation, mostly the cause. Once in the camp, prisoners' fate were no different. Deviously welcomed by an SS commander and his troops, the commander would ask prisoners to line up in two. On the right - young, robust men ready for work. On the left - children, women, old and sick men, deemed useless. Those in the right would live for another day as slaves, and the other, would be asked to "take a shower," a Zyklon B shower. Families, friends and loved ones would see last of each other here.

Germany or the Germans, a far cry from their dark, Nazi history today (we jokingly consider Germany our second European home), have always been efficient. And that efficiency spread throughout the camps, especially Birkenau. The gassing of the prisoners came easy for them, but it was the ridding of the bodies, the burning of the bodies that took longer. Hence, they sought to build more and bigger crematoriums. But the deaths were too numerous to count, numerous than the crematoriums could handle. So the Nazi's burned their bodies on an open fire. And unlike Auschwitz I's crematorium still intact, what was left of Birkenau are ruins. The Nazi's, in hopes of covering up their crime, tried to burn everything down. But the cry of innocent blood were much louder than those of its crackling flames. Escapee's and sympathizers had been secretly taking pictures and passing the horrendous info along to the rest of the world. And by the time the allies came, they already had a general idea of what's going on at these concentration camps before Birkenau finally saw liberation's light.

The sun was at its mid-afternoon peak, the wind dry. The first few groups we've seen earlier had headed back out, replaced by new saddened and stunned faces. Our group slowly dispersed while some stayed with our guide, asking more questions upon questions. I had them too, about those who escaped. How did they do it? How did they not get caught? But those questions were selfish and trivial. I only hope to find some assurance that there must be something good to celebrate on, that amidst its haunted history, Birkenau, took mercy and set others free. But as if Auschwitz knew my heart's content, the tour guide became occupied with other tourists that to wait for her meant missing the bus in half an hour. So Ralph and I decided to explore the rest of Birkenau into the woods. We kept the mood light, joking how the German's are still the same - efficient, but the atmosphere refused to improve, remaining somber. There was a silence that passed between Ralph and I, imagining that the same unpaved road we were trudging on were the same ones, prisoners, workers and Nazi's trudged alike, that the same unpaved road carry strewn human ashes. We passed by guard houses, tall trees, and ponds then hesitated to go even further and peek at the last building standing in the area. The bus might leave without us, was our excuse but deep within, sadness. Saddened by the sound of the eerie air, the cacophony of innocent, hollow cries.

Krakow, Poland in Pictures

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed